Introduction: Consumer Demand for Energy Efficiency

For many Indonesians, indoor comfort comes at a high price: escalating electricity bills driven by air conditioner (AC) usage. A common problem is that while cooling performance may feel poor, energy costs continue to surge. To address this and promote rational energy conservation, the Indonesian Government, through the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM), implemented the Minimum Energy Performance Standards (SKEM) and the Energy Efficiency Label (LTHE) in 2015, initially focusing on air conditioning. The LTHE serves as a critical instrument designed to assist consumers in making informed decisions, functioning as both a standard and a guarantee that products on the market are energy-efficient. However, to ensure that the efficiency promised on the label reflects actual market performance, a robust oversight mechanism is required. This necessitates the establishment and strengthening of an independent national laboratory dedicated to conducting spot checks (sampling) on AC units in circulation.

Evolution of Standards: From EER to CSPF

To understand the necessity of strict oversight, one must look at the evolution of efficiency standards. Metrics have shifted significantly to better reflect daily usage conditions, particularly in hot climates.

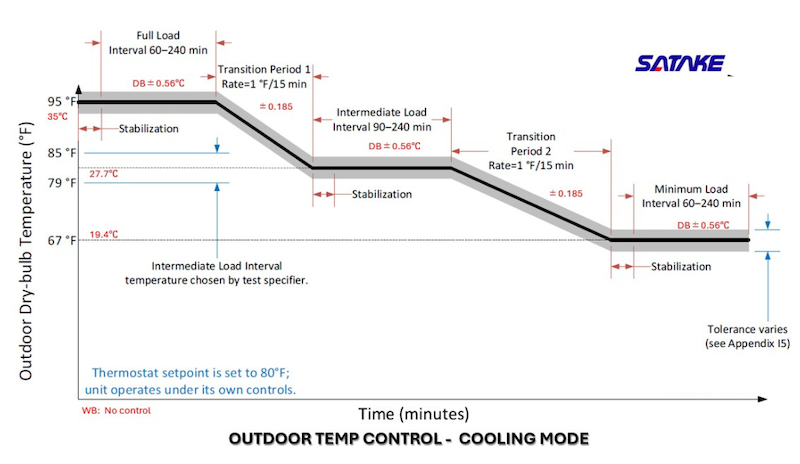

- Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER): Initially, efficiency was measured using EER, which is the ratio of cooling output (BTU/hour) to power consumption (watts) at a constant, standard condition (e.g., 35°C or 46°C. Its main limitation is that it represents efficiency at only a single operating point or peak condition, failing to capture actual performance across a cooling season with varying temperatures.

- Cooling Seasonal Performance Factor (CSPF): To address these limitations, the CSPF was developed. CSPF is defined as the total cooling output removed from an indoor space during active mode, divided by the total annual energy consumed. It is a more realistic metric because it accounts for varying ambient climate data throughout the season and partial load operations—crucial for modern inverter ACs that are more efficient at lower loads.

A higher CSPF indicates better seasonal electricity efficiency, directly resulting in lower utility bills for users and a reduced carbon footprint.

The Critical Role of Energy Labels and the Need for Verification

The LTHE utilizes a star-rating system (up to 5 stars), where more stars indicate higher efficiency based on CSPF values. Mandatory labeling aims to protect and inform consumers. As noted by the Indonesian Consumers Foundation (YLKI), the LTHE acts as a government-supervised manufacturer’s guarantee that the product meets safety and efficiency standards.

While initial certification provides confidence that a 4 or 5-star AC is efficient, consumers require assurance that mass-produced units maintain the same quality as the samples submitted for initial labeling. There is a critical need to ensure no post-certification specification degradation occurs.

Urgency of Independent Spot Checks to uphold the integrity of SKEM and LTHE standards, routine spot checks (sampling) of labeled products in the market are essential. This surveillance must be conducted by a reputable, independent institution with academic standing and government support. An independent national laboratory serves as the guardian of efficiency claims:

- Maintaining Integrity: Spot checks ensure that mass-distributed units meet the CSPF standards indicated on their labels, preserving public trust in the LTHE system.

- Real Consumer Protection: Detecting products that underperform (e.g., a 5-star labeled AC performing at a 3-star level) prevents financial loss for consumers due to higher electricity costs. It acts as an early detection system against fraud or production quality decline.

- Strengthening Regulatory Credibility: Regulatory bodies require support from high-precision facilities, such as psychrometric chambers or Balanced Calorimeters, to validate their oversight. These labs must operate with professionalism, independence, and impartiality.

Standardization Ecosystem and Measurement Validity Challenges Indonesia has a structured standardization ecosystem, with the National Accreditation Committee (KAN) responsible for accrediting conformity assessment bodies (LPK) according to ISO/IEC 17011 standards.

Although several ISO 17025 accredited labs exist, there are concerns regarding inter-laboratory measurement discrepancies and result reproducibility. Consequently, published performance values (as stated on nameplates) may lack significance, raising doubts about guaranteed performance.

A strategic solution involves establishing an independent testing facility to take a central role in proactively supervising and managing accredited laboratories in Indonesia. If a laboratory’s measurement accuracy or reproducibility fails to meet standards, strict actions including the recommendation to suspend operations until improvements are made should be enforced. Given the high proportion of household electricity consumed by ACs, strict compliance with national energy regulations is vital for both Indonesia’s energy security and the global environment. This initiative aims to compel manufacturers to maintain strict discipline in developing energy-efficient products.

Conclusion

The shift from EER to CSPF in Indonesia is a progressive step that offers a comprehensive view of real-world performance. The LTHE star rating is a vital guide for consumers, but its effectiveness hinges on credibility maintained through rigorous market surveillance. The establishment of an independent national laboratory specifically for AC spot checks is a non-negotiable measure for consumer protection. It ensures that the “5-star” promise delivers actual seasonal savings, preventing the market from being flooded with substandard products and ensuring that government-supervised efficiency guarantees are honored. Without robust, independent, and routine spot checks, the risk of consumer financial loss and eroded trust in energy labels remains high.